Home About Robert CV The Good Lord Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: Pentimento Memories of Mom and Me Media Kit Novels Reviews ESL Papers (can be viewed online by clicking on titles) The Many Roads to Japan (free online version for ESL/EFL teachers and students) Contact      |

(Some portions of this book are adapted from my novel Looking for the Summer)

Chapter 6

John had been in Paris for about two months when one day he returned to his hotel to find two Asiatics at the front desk trying desperately to communicate a message in English to the clerk, who spoke only French. John had learned a little French by then and was able to give a crude interpretation to the clerk. The Asiatics were very happy and invited John to have a cup of tea with them at a cafe across the street. Introductions were made. One of the men was an Iranian businessman named Hamid. The other was an Afghan motel owner named Abdul. Both were in Paris on business trying to sell carpets. They were disgusted with Paris because the people seemed cold and indifferent to them. John was the first person who had helped them. They were so impressed with the friendliness John had shown that they invited him to return with them to their countries. Hamid said that life in Iran was not expensive and it was easy to find an English teaching job. Despite his affection for Paris, John's money was dwindling rapidly and the chance for adventure in a country he knew little about appealed to him. He accepted the invitation. Hamid and Abdul first had to visit a friend in Germany. John joined them two weeks later. Hamid bought a new BMW car, which he would later sell in Iran to cover the cost of their journey. Abdul would take a train after John and Hamid departed. Hamid and John spent a day passing through the Swiss Alps. In the beginning Hamid's driving frightened John. Hamid was a madman behind the wheel, flying along the mountain roads as if in a grand prix road race, taking chances passing other cars at high speeds on blind corners. He laughed at John's fear and told tall tales of his adventures as a driver in the Iranian military. Late that night they arrived in Milan, Italy and took a room. The next day the journey continued east through a thick fog to Trieste. They entered Yugoslavia. Hamid drove the BMW as if jet propelled. John took notes on the passing scenery: distant blue hills, scattered farms, stone-and-brick houses, peasants pacing the sides of the road with hoes slung over their shoulders. They continued into the night toward Bulgaria, the BMW rushing past Soviet military trucks on a winding, rocky road. They arrived at the Yugoslav-Bulgarian border early in the morning. A Bulgarian military guard detained them for two hours before granting their visas at dawn. They entered Sofia. Military transport trucks moved slowly along cobble streets. There were no smiles on the faces of the men and women shoveling dirt on the sides of the road, nor on the faces of the ubiquitous police. They headed into the country, all the time approaching the East over dirt roads and cobble roads and through peasant villages and industrial towns. Everywhere they passed they saw old peasant women with slouched backs, bundled in woolen scarves, socks, and sweaters, packing hoes over their shoulders, pacing slowly in groups of three and four to the fields. They entered Istanbul, Turkey, where John got a visa for his entry into Iran. They spent a day exploring the activity of the streets, visiting Mohammedan mosques with high-reaching minarets, and haggling with venders and merchants of all types. The streets were full of older American cars, horse carts, all kinds of carts competing for limited, dirty space. They saw thin, dark, hungry children playing everywhere. They headed east toward Ankara. The road from Istanbul to Izmit was a solid stream of trucks and buses carrying great amounts of supplies and goods from all parts of the West to Iran. An army of vehicles carried gas, food, construction equipment, pipes and girders, tires, wood, people, other cars and trucks, everything imaginable. On this road Hamid proved his ability as the self-proclaimed best driver in the East. He swerved to the left and right to pass trucks in front of them, paved new lanes in the dust, narrowly missed oncoming traffic, squeezed between huge trucks where there seemed no space, and passed to the extreme left of trucks passing other trucks. All the time he weaved and honked, braked and shifted gears furiously, and screamed at the other drivers. Finally, they arrived in Ankara and spent the night. From Ankara to the Turkish-Iranian border was roughly 1,500 kilometers. Hamid told John that the next section of road was the most dangerous part. Kurdish bandits were said to be in the mountains and would stop cars travelling alone. It was best to drive during the day and in groups of three or four cars. They left Ankara on a sunny morning. Ahead were sun-baked hills with stone-and-mud houses scattered throughout. In the distance lay looming, white mountains. They climbed higher into the hills. Strong winds were howling. They passed sparse, wind-sculpted brush, thin patches of snow, and an occasional mountain village where the soil had been worked by hand. They headed into the high eastern mountains, the road rising to summits where wind flurries were a blinding white, then dipping to lower elevations where boulders of slush and white mud crashed against the sides and frame of the car. At one point they passed a mountain village of about 25 rock huts covered with snow. John wondered how these mountain people could survive the winters. It took Hamid and John two more days to reach the Iranian border. In that time they once encountered Kurdish bandits on horseback, passed a wreck involving a bus and a truck near Erzurum, and saw several trucks forced off the side of the road. A blizzard forced them to stop for several hours before they could start moving again. They covered themselves with their sleeping bags and waited for the storm to subside. When they were able to start again the road became worse, filled with large potholes. Trucks approaching from the opposite side splattered the BMW with slush and thick, brown mud. One truck sprayed them with small stones and the windshield cracked. Finally, they dropped out of the last elevation to the lower ground. They were out of the snow. The road was muddy, but getting better. They passed two more villages of mud hovels where wild dogs roamed the streets. When they reached the border, hundreds of cars and trucks were backed up. They waited an entire day before being allowed into Iran. ***** Three days later they were in Hamid's home in the holy city of Mashad. Hamid was welcomed home as if he were a conquering hero returning from distant lands. His mother, father, three brothers, and two sisters treated John with much warmth and hospitality. In the beginning there was much for John to become accustomed to: the squat toilets, sitting cross-legged on the floor for long periods of time, the sound of the Farsi language, not being able to see the faces of the women, who were required to wear the chador in the presence of a non-Muslim.

The time soon came when John could no longer stay with Hamid's family. It was uncomfortable for them, particularly the women, to have to share their home too long with a non-Muslim. The schools would not open for a few more weeks, so Hamid introduced John to some carpet sellers in the bazaar. John could obtain a small commission for luring foreign tourists to their shops. This job was known as "street hawking." Another street hawk by the name of Ali offered to share his room with John. Ali had come to Mashad as a boy after living his first few years in a family of shepherd nomads. He had picked up portions of five languages from making his living on the streets. His room was located on the bottom floor of a two-storey, brick-and-mortar structure near the bazaar. John began to spend his days with Ali walking the streets near the mosque and the bazaar. Ali was known in all the shops. He was the quintessential guide. He knew where to get the best prices, both on the black market and in the shops, as well as find the best and cheapest hotels, entertainment spots, jewelry, carpets, and transportation. Mashad was a clean city

undergoing great changes. Old buildings were being

torn down and modern buildings were replacing them

on nearly every street. There was activity

everywhere. Women in chador strolled by

sensuously, swarthy men in turbans lined the

streets, peddlers pushing carts of fresh fruit and

nuts hawked their goods, children laughed and

played, cars and horse-drawn carts paced to and

fro, and men squatting on their haunches spread

out their knives, bracelets, tools, pipes,

samovars, and rings of precious stones before them

for tourists to see. Sounds from the various bread

shops, grain shops, copperware shops, and carpet

shops filled the air. John walked about in a daze,

soaking in the atmosphere of the ancient, holy

city. In the evenings Ali's friends often stopped by the room. They spoke of falling in love with European women they had met on the streets. They implored John to write love letters in English for them. There was an unspoken paranoia about them. When they spoke about their dreams, they did so in a low whisper as if an enemy might be listening. Many expressed a desire to marry a European woman. It was the only way they could obtain a passport to leave the country. They had a strong fear of the obligatory military service and the punishment given those who refused to serve. When John pressed them for reasons to explain this, they said it was forbidden to discuss politics or religion with a foreigner. Meeting Ali's friends, hearing their stories, and seeing the fear they felt about resisting the government's authority caused John to reflect deeply about his own anti-war and prison experiences. He had suffered psychologically after his release from prison and for a long time had succumbed to believing that he really had been a coward and an "undesirable." He had sought to escape the country of his birth and find another life abroad. He could empathize with these young Iranians and their paranoia and dreams of escape. He wanted to explain to them how he had found solace, therapy, and a means of venting some of the insanity of his thoughts through the medium of writing. He wanted to give them some of the hope and optimism he had discovered on the road, but the realization that he was powerless to do so hit him hard. He was again a man without a home. The days dragged by. An inexplicable emptiness came upon him. The excitement of being in a different and strange land was replaced by boredom and restlessness. He began to think obsessively about death. The idea of walking the streets anymore became repulsive. For days he spoke to no one but Ali, who left early in the mornings and returned late at night. In the gloom of the room John felt like a prisoner alone in a cell. The folly of his past filled his thoughts. Nightmares full of death visions began to plague him. One morning, while

bathing his face in cold water, John looked at his

reflection in the mirror and saw a stranger

staring back. He knew that sometime soon he would

have to move on again. Review for Chapter 6 I. Comprehension Questions Chapter 7 A few days later John went to the Afghan consulate and got a 30-day visa. He called Hamid to thank him for all his help and his family's kindness, then said goodbye to Ali. The next morning he boarded a bus to Herat, anxious to see what further adventures awaited him. He crossed the Iranian-Afghan border and proceeded to Herat, a city of low, brown adobe huts clustered tightly together and enclosed by mud walls and towers. The first thing he noticed when crossing into Afghanistan was the conspicuous absence of Western influence. It was like stepping into the pages of the Old Testament. Time had changed nothing. The people of Herat in the narrow bazaar streets had a distinct peace and dignity. They moved about their work as if it did not matter, as if it could be done either the next day or the day after. The coppersmiths, the cobblers, the saddlemakers, all the various shopkeepers worked as they had for centuries. There were some shopkeepers who, in the intense heat of the afternoon, dozed in their stalls.

John spent two days in Herat and left the following morning on a bus. The sunrise cast varied tints from golden brown to violet on the low, distant mountains. The bus entered the open desert. John was the lone foreigner on a bus loaded with Afghan men. A sea of bobbing turbans atop dark, proud faces filled the bus. Across the glaring distance there was nothing but an empty stretch of desert. They came to Kandahar, Afghanistan's leading commercial center. The people had a freer air about them than those in the villages the bus had passed. The city had much less the atmosphere of a remote fortress than Herat. They stopped for tea in a cafe that was full of smoke, full of men, full of rich, masculine smells. The bus continued toward Kabul, stopping three times during the day for the Afghans to roll out their prayer carpets and, facing Mecca, pray. At Ghazni they witnessed a sunset that bathed the eastern mountains in a fiery red and deep violet. It lasted but a few minutes before the night grew dark and solemn. Two hours later they arrived in Kabul, the capital city. Two of the Afghan passengers helped John get a taxi to Abdul's motel. Abdul was surprised and pleased to see John. He introduced John to his partner and brothers, then showed John to a room. He brought some tea and the two visited for an hour. The city of Kabul was

located in a large, fertile plain surrounded by

high hills rising into the Hindu Kush mountains.

The whole of the city seemed a mass of mud huts,

although the newer part of the city bore signs of

modernization: apartment buildings, a hospital,

and a university. There were many wide streets

lined on either side with poplar and mulberry

trees. There were also many gloomy, narrow lanes

that even in daylight were so dark one had to walk

slowly and take care not to fall into a

ditch. John spent most of his time relaxing, reading, and walking the streets around the central bazaar area. In most places the streets were full of primitive wooden structures on which were laid mats of hemp. There were rows and rows of stalls on which the traders squatted cross-legged. Those who could not afford to buy a stall sat on the street corners and sold their goods. It was always crowded. In the midst of all the activity passed donkeys laden with wood, brick, and straw. Camel caravans passed slowly. Riders on horses pushed their way through in a domineering manner. Abdul's motel was a run-down place with a kitchen and about 20 rooms filled with tattered carpets and beds of rope called charpoy. The people who frequented the motel were a strange sort. They were mostly of the younger, vagabonding set, Europeans who had come east to the lure of cheap living and an easy access to drugs. They were reminiscent of the drifting bohemians John had met on his journey through Europe four years earlier. Those people had instilled in him an excitement with their talk of literature, philosophy, and revolution. The people he now found himself surrounded by, although much the same in appearance, were a more decadent type. They had faded into a vegetable existence. They talked only of drugs. They smoked hashish all day, stared into space, and made friends only for a meal or a bus ticket. Abdul was busy much of the time, but he managed to get a few days off and invited John to spend some time with his family in the desert outside Ghazni. When they arrived by jeep, they saw sheep and goats grazing in the plain while a few powerful mastiffs kept watch over the village. The men were plowing the sparse fields and threshing corn. The women sat in front of the tent-like huts knitting and playing with the children. Abdul introduced John to his mother and father. John and Abdul spent four restful days in the village before returning to Kabul. John was treated like royalty. Great meals of rice, lamb, bread, tea, and fruit were served. One of the lambs had been butchered upon their arrival. In the evenings they sat around a fire, shared a nargile of hashish, watched the stars, and listened to the somber sigh of the earth. The time came for John to continue east. His 30-day visa would soon expire. He and Abdul embraced with a genuine fondness, knowing they would never see each other again, but glad to have been able to share a portion of their lives together. ***** John took a bus into Pakistan as far as Rawalpindi, where he bought a train ticket. The ride through the dusty Indus Valley was long, hot, and uncomfortable. There were many stops where soldiers either boarded or got off the train. He spent the night in a cheap motel in Rawalpindi and the next day took a crowded train to Lahore. In the brilliant sunshine the train swept past rice fields and stagnant pools full of white lotuses and standing herons, past people slapping pie-shaped, cow-dung patties onto the sides of mud huts to dry, past men with bullocks and submerged plows preparing rice fields for planting. In the different train stations were fruit venders and their carts and janitors in white uniforms sweeping the platforms with palm fronds. Each town had its shantytown by the railroad tracks, smaller towns of grass huts, cardboard shelters, pup tents, hovels of paper and twigs and cloth. Everyone in these shantytowns was in motion. The train arrived in Lahore. Processions of rickshaws, pony carts, hawkers, and veiled women filled the narrow lanes. The larger streets were congested with swarms of jostling people. Recently there had been an uprising against the Bhutto regime for allegedly rigging the elections. There was now a curfew with the military patrolling the streets at night. Late that night, as he went to sleep in another cheap motel room, John heard muffled sounds of gunfire coming from the streets. He crossed the border into India the next day. There was a long wait at the border as the customs officials took their time examining every passenger's baggage. The train arrived in Amritsar in the early evening. There was no train to Delhi until the next morning. John slept that night on a bench in the station waiting room. The next day John arrived at the station in the old section of Delhi. A seething swarm of people surrounded the passengers as they got off the train. Everywhere skinny, brown rickshaw drivers and hawkers of cheap goods were clamoring for attention. John allowed himself to be swooped up by one driver, who took John's dufflebag, hooked it on his bicycle rickshaw, and pedaled John to a section in a bazaar area where John could find a cheap room. They rode past entire communities living on the streets. Women in tattered rags with cracked feet and rings in their noses stood cooking pots of vegetables over smoky fires. Children ran here and there. The narrow, winding streets and wide bazaars were littered with debris and thick with intimate odors. Cripples walked the streets alongside half-naked natives. Thousands of people with rickets, leprosy, skin diseases, and bloated bellies lined the filthy streets. Vehicles of many types competed for limited space. John found a room in an old, ramshackle motel. A single window overlooked a narrow street in the bazaar. The heat in the room was suffocating. It was impossible to sleep soundly. For the next week John walked the streets. Everywhere he saw poverty, hunger, disease, violence, and nightmare misery. He walked through the refuge quarter of the city. He went there every day to stare at the chained-off society, as if it were a perverse circus side show. He was lured by its air of unreality. The people lived in houses built of tin and boxes, hideous things, hotbeds of epidemic. The strange thing was how the older people had grown reconciled and seemed almost glad of their misery. They were scattered all about in every pose of contorted collapse, like in a picture of a massacre. There were people with catalepsy, with tuberculosis, with syphilis, with worms of all sorts, with eye diseases, with many saddening things. Some lay prostrate about the chained-off streets, their faces gaunt and colorless. When they closed their eyes, they looked as if they were dead. John was struck by the extraordinary stoicism with which these people bore their sufferings. He felt humble and meek, filled with self-disparagement, abasement, and a despair that would not go away. As he returned each night from these visits to the purgatorial streets, he inevitably stopped at the same stall in the bazaar. Exhausted from destroyed emotions and the heat, he bought fruit or liquid refreshment. The shopkeeper was an old, wrinkled man who had seen many generations of suffering and still held his head high, composed like a Buddha. The man's impassive repose was like a display of great dignity. John was overwhelmed by the abstracted silence of this man. One night, in a moment of excruciating self-pity, John seized the old man's hand and wrung it with all the force of his gratitude. The shopkeeper simply smiled and passed his hand gently over John's head. Dysentery overtook John.

He lay for days in a sweating fever on the

charpoy, the sole piece of furniture in his room.

He became like the prostrate death-forms of the

streets. He was so weak he could not lift his body

and lay in the sticky warmth of his involuntary

excretions. He prayed for death, for deliverance

from the agony of existence. At times he was

barely conscious of voices murmuring around him

and of someone pouring water over his head.

Finally, the fever broke. In his weakened

condition it was all he could do to drag himself

into the streets to the shopkeeper's stall. The

old man gave John tea, fruit, and yogurt in

silence. John's strength gradually returned.

Review for Chapter 7 I. Comprehension Questions Chapter 8 John had about $300 remaining. He bought a bus ticket to Calcutta, where he hoped to find work aboard a freighter headed to the U.S. He left Delhi early in the morning. The journey lasted two full days. One vista shifted into another, a dizzying displacement of hill and air, of haze and all the shades of green and brown. All along the road were animals and people. Bandy-legged men in the bus spit betel juice from their red lips through the windows, as if in derisive comment on the abject condition of life. Calcutta was a mass of tenements, hovels, temples, mosques, shrines, warehouses, shops, and factories. It was worse than Delhi. The smoke of tens of thousands of cow-dung fires used by the inhabitants of the streets for cooking hung over the city. Everywhere in the overflowing streets lay the squalor of diseased life and morbid death. John saw one man leap in front of a train pulling into a station. After the train passed, the man, his legs amputated at the waist and bleeding profusely, lay on his back with his hands extended upward. His shrieks were wild and sounded like a madman's laughter. He finally collapsed, blood flowing fast from his mouth, his eyes open and staring at the sky. John passed through a leper colony that was on the other side of a railway bridge. Not far away was a vast garbage dump. Some of the lepers lay on beds inside mud huts with their limbs bandaged. One boy sat against an outside wall, his arms and legs smeared with a blue ointment. Next to him was another child whose finger stumps were raw and bleeding. There was a woman using the grey stump of her hand like a wooden spoon to stir a pot of steaming liquid. A few nuns from Mother Teresa's Missionaries of Charity, the Nirmal Hriday, came that day bringing bandages, food, and cats to keep at bay the garbage dump rats that sometimes crossed over to the colony to chew on leprous limbs. John followed the nuns back to the Nirmal Hriday. A small but clean building was crammed with rows and rows of stretcher beds with dying patients. The patients lay very still, blinking and sometimes reaching for food. The nuns moved continuously down the rows of beds, dishing out food to those able to eat, shaving the heads of those with lice, dressing the sores of the rancid ones, and cleaning up the ones who soiled themselves involuntarily. There was one man with a gangrenous leg wrapped in rags who was taken outside because of his terrible stench to have his leg rinsed. The water caused the blood to flow over the green flesh. Bits of bone and muscle dropped off the leg. A crow flew down and picked up a piece of bone that had fallen from the leg. John vomited and left. He walked along the Hooghly River. It was silted badly from the ashes of cremated bodies. Garbage lined the streets. More than once John saw, resting in the piles of garbage, a dead baby whose skin was parched and cracked. He bought a bottle of wine from a black market dealer, got drunk, and passed out on the streets. He awoke the next morning with a pounding headache. The morning heat was already piercing and insufferable. He bought fruit and bottled water from a street vender and watched the wretched masses. A new desolation crept over his soul, a wild, aching loneliness. He felt weak and hollow within. He found a park with some trees that provided shade to sit under. He stared incomprehensibly at the sky. What had he learned from this journey? What had he gained? A deeper awareness of the suffering of mankind? He knew only that his own personal suffering was nothing compared to the swarms of creatures he had seen in Delhi and Calcutta. He could no longer feel even pity. There was no room for pity, not where all required it. He thought again of the sight of one man he had seen lying on the hot pavement with a wide, open wound across an exposed leg in which hordes of maggots were feasting on the green insides. The man had been completely composed, as if the leg were a separate entity and not attached to him. It came to John that what he had seen was not the decay of a single man, but the symbolic decay of a whole lifetime of hopes and beliefs built up during John's years of wandering and now, in the swift passing of thoughts, utterly destroyed. John sighed heavily, got up, and trudged toward the docks. It was time to go forward, to leave the baggage of Asia behind, to find a new life. ***** By the time John arrived back in the United States from his journey around the world, he was a physical and emotional mess. The reverse culture shock he experienced could not have been too different from that of the Vietnam War veterans who had fought in the jungles of Southeast Asia and returned to an America indifferent to the revelatory changes they had undergone. He felt alienated, as if he had had a secret experience, had discovered an extraordinary land from which he could never fully return to give his knowledge to his fellow countrymen. There were times in the ensuing months when John, now 26, felt as if he had died and found himself reborn in an altogether alien country. Where once there might have been a semblance of political, philosophical, and religious ideas and convictions to hold on to for guidance, there were now giant question marks attached to everything he thought, everything he saw, everything he experienced. There was only one truth for him: the period of time from which he had just departed. John now began a five-year period of rambling around the United States. He spent a winter in Seattle working as a stevedore and a mailman, then picked up the cooking trade working in restaurants up and down the West Coast before heading to Louisiana and Florida. Everywhere he went he was pursued by the memory of his Asian experiences. A misanthropy grew within him as he dwelled too much on the disparities between Asia and the United States. He came to believe the United States was nothing more than an adolescent nation in need of waking to the realities of his Asian death visions. He eventually landed in Texas and was hired as a steward for two separate oil production rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. He would rotate between Corpus Christi and Galveston, where helicopters transported him offshore, and work a two-week shift on each rig with a week off in between. He saw many wonders in the Gulf. The colors of the sea and sky changed hourly like a vast, wonderful kaleidoscope. There were days when the sea and sky blended together in a warm satin blue and changed progressively to sapphire and indigo. At sunset the coast became a purple line and the few clouds rust-colored as the crimson sun sank slowly below the horizon. There were other days when the clouds were leaden, the sky black, the sunsets a long line of burning vermilion like a forest fire in the distance between a black sea and sky. There were often nights when a huge depth of blackness hung over the rigs and strong winds swept at them from out of a vast obscurity. He would spend these nights reading in his bunk, feeling the pulse of the generators on the deck below like the beat of the rig's heart, the gale winds howling and scuffling about gigantically in the darkness.

A newborn faith and optimism began to grow in his heart. He was ready to write another book. The two books he had written previously were failures, but he saw them now as a necessary part of his apprenticeship. He had saved up some money and could afford to take some time off to concentrate on writing again. A letter came from a writer friend living in Maui, Hawaii. John was invited to come stay as long as he wanted. He quit his job, packed up his belongings, and bought a plane ticket to Hawaii. John spent a relaxing few months in Maui. There were the lazy afternoons swimming in the ocean and driving in the high hills of Haleakala, the volcanic crater that rose above the island. There were the spectacular views from up high of the sparkling Pacific and the thick foliage of the lower valleys. There was the colorful array of flowers speckling the gardens of the residential areas. There were the bright beaches, the towering palms, the vast stretches of sugar cane bristling in the trade winds, and the blue-green fields of neatly furrowed rows of pineapple. A distortion of time permeated John's existence. The writing did not progress well. John grew fat and lazy. Another change was called for. He felt the need to be jolted into a different reality. When his friend was called back to the mainland to promote a new book, there was no need for John to stay on the island. The friend suggested John go to Japan, where he could probably find work as an English teacher. The friend gave John some names and addresses of places John could stay until getting settled. For a long time John had

dreamed of living, working, and studying in a

foreign country. During all his journeys abroad he

had respected and envied those who spoke more than

one language. He had vowed one day to learn to

speak a foreign language himself. Now it seemed

there might be a chance for him. On a January day,

two weeks after his friend had returned to the

mainland, John was on a plane to Osaka. He had

only $100 remaining, but there would be some

income tax money returned to him in the spring. He

had been in tighter situations before. He was

ready for one more adventure. He had faith in

himself. He knew he would ultimately survive.

Review for Chapter 8 I. Comprehension Questions

a. John met Hamid and Abdul. Afterword John's first few months in Japan brought with them a dizzying development of events. Within a week of his landing in the Osaka-Kobe area he had found a job through the English newspaper classified ads. He began teaching at a conversation school, where he met a Canadian woman whose Japanese roommate helped him find a cheap, two-room apartment. The apartment had no bath, so he went to the local public bath every night. John also began studying Japanese on his own. Within a few months he had made many friends in his neighborhood and had joined a softball team. Spending time with the members of the team, as well as going to the public bath regularly, allowed him to gain much speaking and listening practice. His study of Japanese helped him gain a better understanding of the problems his students faced in studying English. A sense of stability entered John's life. For many years he had dreamed of being able to live, work, and study in a foreign country. That dream was now coming true in Japan. He had a job he enjoyed, the blessing of many friends, and the challenge of adapting to life in a foreign land. Two years passed. He would eventually have to change the type of visa he had if he wanted to continue living in Japan. He began seriously contemplating his future. He had reached the point where a fundamental decision had to be made. If he committed himself to a life in Japan, he would have to make some serious efforts toward a career. It was obvious he would never make a living as a writer. He had failed to sell a single book. He liked his job at the conversation school, but he had reached his peak in salary and position. He had no academic qualifications to rise above his current situation. He decided to get a degree in the teaching of English as a foreign language. He found an American university that had a branch school in Tokyo and offered correspondence courses for obtaining bachelor's and master's degrees. He applied for and was accepted into the program. Over the next few years John continued to work and study hard. He eventually fell in love with and married a Japanese woman. He went on to get his master's degree, a permanent resident visa, and a full-time teaching position at a Japanese university. Throughout his years in Japan he has had many trials and tribulations, but today he is relaxed and comfortable with the life, language, and people of Japan. He is a happy man with a sense of purpose, direction, and fulfillment. After travelling many roads and spending many years of searching, he finally found his niche in life. In his spare time John

continues to write novels. His wife works as a

teacher and translator. His greatest reward in

life is seeing students discover the joys of

studying a foreign language and communicating in

it. He believes that dreams can come true if one

works hard enough and has a lot of patience. His

own life is proof of that. Review for Afterword I. Discussion/Essay Questions Note: Teachers who

would like to obtain a copy of the answer sheet for all

end-of-chapter questions can contact me via e-mail

at:

robert AT robertwnorris DOT com Cover image by Professor Yoshio Tanaka, Saga University

B-52 photo by Aerospaceweb.org - http://www.aerospaceweb.org/aircraft/bomber/b52/pics02.shtml Redwoods photo by 3-D Viewmax - http://www.3dviewmax.com/ Matterhorn photo copyright by Frank Carus - http://www.ski-zermatt.com/mattnet/features/matterhorn_climb/photo0.htm The David photo by CGFA: A Virtual Art Museum - http://sunsite.dk.cgfa/michelan/p-mechela2.htm Holy Shrine of Imam Reza photo by Silk Road Tours - http://silkroadtours.com/SilkRoadTours/Album/Iran%20photoes/Mashad/Mashad.htm Three women in chador photo copyright by Vanderven - http:vanderven.org/pix/ym/chador.htm Group of Afghan men photo copyright by Luke Powell - http://cweb.middlebury.edu/cr/powell/afghanistan/ Kabul photo by Qazi brothers - http://www.afghan-web.com/ Oil rig photo copyright by Greenpeace/Dott - http://www.greenpeace.com/

Copyright (c) 2024 Robert W. Norris. All Rights Reserved |

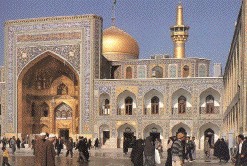

There was much visiting to be done.

Hamid had many cousins, aunts, uncles, nephews,

and nieces, all of whom lived in various parts of

Mashad. Hamid often took John to visit friends in

the bazaar. From there they went for walks around

the Holy Shrine of Imam Reza and the mosque where

the tomb of the prophet was laid. John was

impressed by the generosity, kindness, and

gentleness of everyone he met.

There was much visiting to be done.

Hamid had many cousins, aunts, uncles, nephews,

and nieces, all of whom lived in various parts of

Mashad. Hamid often took John to visit friends in

the bazaar. From there they went for walks around

the Holy Shrine of Imam Reza and the mosque where

the tomb of the prophet was laid. John was

impressed by the generosity, kindness, and

gentleness of everyone he met.

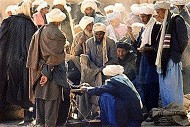

The Afghans

were a virile people. The attitude of the crowds

in the bazaar was of a mild disdain. John saw few

beggars. The men were proud of bearing, savage and

distinguished in appearance, and they met every

man's eyes on the level with a straightforward

glance. Their faces carried an expression that

showed no fear. Their bodies were strong and

supple. The few women seen in public were shrouded

in full-length chadors with embroidered masks.

The Afghans

were a virile people. The attitude of the crowds

in the bazaar was of a mild disdain. John saw few

beggars. The men were proud of bearing, savage and

distinguished in appearance, and they met every

man's eyes on the level with a straightforward

glance. Their faces carried an expression that

showed no fear. Their bodies were strong and

supple. The few women seen in public were shrouded

in full-length chadors with embroidered masks.

Gradually, his

misanthropy left him. He came to view his fellow

workers as noble men. Sometimes after supper they

would retire to the top of the rig, 150 feet in

the air, and watch the shifting moods and colors

of the sea. The sound and rush and wonder of

nature before them served to create an atmosphere

of trust and brotherhood, a bonding of working

individuals in a special environment. Many of the

men were Vietnam War veterans. On the top of the

rig, with the splendor of a star-filled sky above

and the sound of the sea below, these men's

confessions of things seen and done in the war

were uttered and carried off by the rushing wind.

Gradually, his

misanthropy left him. He came to view his fellow

workers as noble men. Sometimes after supper they

would retire to the top of the rig, 150 feet in

the air, and watch the shifting moods and colors

of the sea. The sound and rush and wonder of

nature before them served to create an atmosphere

of trust and brotherhood, a bonding of working

individuals in a special environment. Many of the

men were Vietnam War veterans. On the top of the

rig, with the splendor of a star-filled sky above

and the sound of the sea below, these men's

confessions of things seen and done in the war

were uttered and carried off by the rushing wind.